Summary

The Rohingya of Myanmar have been among the most persecuted people in the world. Genocidal attacks at the hands of the Myanmar military starting in August 2017 caused more than 770,000 Rohingya to flee. The challenges Rohingya face residing in the largest refugee settlement in the world in Bangladesh and the ongoing risks to the estimated 600,000 Rohingya remaining in Myanmar are well known. Less is known about the Rohingya who have fled to other countries throughout the region, including at least 20,000 Rohingya in India. This population is a stark example of both the secondary effects of the Myanmar military’s abuses and the failure of countries throughout the region to uphold the most basic of protections for this population.

The Myanmar military leadership responsible for the genocide launched a coup in February 2021, resulting in civil war and widespread human rights abuses of the civilian population. The prospect of a safe return for the Rohingya to their homeland remains remote. Addressing these challenges will be complex and difficult; but providing true refuge to those who have escaped genocide should not be. Yet Rohingya in India are officially labeled as “illegal immigrants” and face troublesome restrictions. These include limits on freedom of movement and access to education, basic health and legal services, and formal employment opportunities. Further, the Rohingya in India face growing anti-Muslim and anti-refugee xenophobia and live in constant fear of detention and even deportation back to the genocidal regime from which they fled.

India prides itself as the world’s largest democracy, but a true test of any democracy is how it treats its minorities. India has a history of providing refuge to various groups and has endorsed the Global Compact on Refugees – an agreement aimed at increasing responsibility-sharing and finding new solutions for refugees. In 2023, India chairs the G20, an influential forum of the world’s most rich and powerful countries. India will also participate in the Global Refugee Forum in late 2023. Failure to uphold basic standards of protection and refuge – let alone forcing genocide survivors back into the hands of the perpetrators – would undercut India’s aspirations to global leadership.

Displaced and Detained – Rohingya in India

Fortunately, India does have a robust legal system and civil society working on behalf of the Rohingya. Several organizations and individuals within India have introduced cases or challenges to government policies in India’s courts. Yet those who speak out for the Rohingya are being threatened, particularly with loss of permission to access foreign funding. Such voices should be supported, not constrained.

For the United States, encouraging countries like India to protect the Rohingya should follow naturally from its official determination that the Myanmar military is responsible for genocide against the Rohingya. The United States has been a leader in providing humanitarian support for Rohingya, including in India. But it must do more to urge countries like India to protect survivors, to provide access to basic services, and to empower them towards what U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken called “a path out of genocide.” That applies to Rohingya in Myanmar, in Bangladesh, in India and wherever they are seeking a better life for themselves and future Rohingya generations.

Recommendations

Adopt a national law on refugees and asylum seekers or pass the Asylum Bill 2021, which was first introduced in the parliament in 2015. This bill would establish an asylum and refugee system, based on international obligations and the principles of the Indian Constitution.

Establish the legal status of Rohingya in India and their right to basic services including education, employment, health care, bank accounts, and SIM cards. This could be done through provision of special Aadhaar biometric cards or recognition of UN Refugee Agency (UNHCR) cards as a valid form of identification for accessing such services.

End arbitrary and indefinite detention of Rohingya, establish special courts and tribunals to hear cases of detention of refugees, and allow UNHCR access to all detained migrants to determine their refugee status and protection needs. India’s National Human Rights Commission should work with the UN Office of the High Commissioner on Human Rights to carry out an investigation of detention centers in India.

Refrain from deportation of Rohingya and other refugees from Myanmar in violation of its international legal non-refoulement obligations.

Release guidance from the central government clarifying the right of Rohingya to access government schools and hospitals. Promote girls’ education and extend access for Rohingya to secondary and university level education.

Allow space for civil society to work with the Rohingya in India including by supporting refugee-led organizations and ceasing threats of withdrawal of Foreign Contribution Regulation Act (FCRA) permissions that allow organizations working with refugees to receive foreign funding.

Provide search and rescue for Rohingya boats when reported in Indian waters and work with regional partners to ensure safe disembarkation, access to UNHCR and asylum claims, and refrain from detention and refoulement.

Pressure Myanmar’s military junta to end persecution of the Rohingya, to recognize their citizenship rights, and to cease broader abuses and attacks on civilians. Such pressure should include cracking down on companies doing business with or supplying arms to the junta.

Engage India at the highest levels, including a visit by the High Commissioner for Refugees, toward refraining from refoulement and indefinite detention, facilitating resettlement, and allowing access to migrants in detention centers to determine their refugee status and protection needs.

Support and fund refugee-led and local organizations that work on provision of services for refugees and on protection and legal assistance of Rohingya detained in India.

Raise concerns over detention, deportation, and status of Rohingya in high-level engagements with India including when Prime Minister Modi visits the White House as expected in the summer of 2023 and when President Biden attends the G20 Summit in New Delhi in September 2023.

Urge UNHCR to take a stronger stance against government intimidation and restrictions on activities in support of refugees. Support NGOs facing such intimidation through private and public engagement with Indian officials.

Offer and encourage other countries to offer resettlement opportunities for Rohingya in India and press the Indian government to allow for exit visas and further resettlement to third countries including the United States.

Provide additional funding to NGOs and local civil society supporting the Rohingya and other refugee populations in India, including protection and services for women and girls.

Methodology and Research Overview

The Azadi Project and Refugees International partnered on a research trip to Rohingya refugee settlements in Delhi and Hyderabad, India in February and March 2023 to assess the conditions and challenges facing Rohingya living in India. The team interviewed Rohingya refugees, refugee-led organizations, UN officials, local and international NGOs providing humanitarian and legal assistance to Rohingya, and other experts. This report is further informed by previous research and interviews by The Azadi Project in Chennai, Delhi, and Hyderabad in 2022 and 2023 as well as several years of research by Refugees International on challenges faced by Rohingya in Myanmar, Bangladesh, Malaysia, and Thailand.

Background

The Rohingya people have suffered decades of persecution in Myanmar, including a series of crack downs by the Myanmar security forces in the 1970s, 1990s, 2012, and 2016-17 that led hundreds of thousands to flee the country. The failure of successive Myanmar governments to recognize Rohingya as citizens has rendered them stateless – without the direct protection of any country, often denied basic services, and more vulnerable to exploitation. The attacks starting in August 2017 caused more than 770,000 Rohingya to flee to Bangladesh. These attacks have been recognized by the United States as genocide and crimes against humanity. The same military responsible for those attacks launched a coup in February 2021 that has led to widespread attacks on civilians and ongoing fighting with armed resistance groups across the country. These events have further diminished the prospects of safe return of Rohingya.

The majority of Rohingya refugees, nearly 1 million, are now living in the largest refugee settlement in the world in Bangladesh. Tens of thousands live in other countries around the region, including Malaysia and India, and to a lesser extent Indonesia and Thailand. The context of the Bangladesh camps has been extensively covered, including in past Refugees International reports. The focus of this report is on the lesser-known population of Rohingya refugees living in India.

Estimates of the number of Rohingya living in India vary widely. UNHCR has registered more than 20,000 Rohingya refugees. The last public estimates by the Indian government in 2017 put the number at 40,000. The Rohingya population in India is a mix of those who arrived following earlier periods of persecution and those who have arrived more recently from the camps in Bangladesh. At least 13,000 Rohingya refugees entered India between 2012 and 2016, mostly from Bangladesh. Recently arrived refugees told the team that they left Bangladesh to come to India because they were not given all the benefits that earlier refugees received, including shelter and rations at the refugee camps. Deteriorating conditions in the Bangladesh camps, including increased incidents of targeted attacks and killings by radical groups, have also motivated some Rohingya to leave for India. Others, facing hardship in India, have chosen to return to Bangladesh.

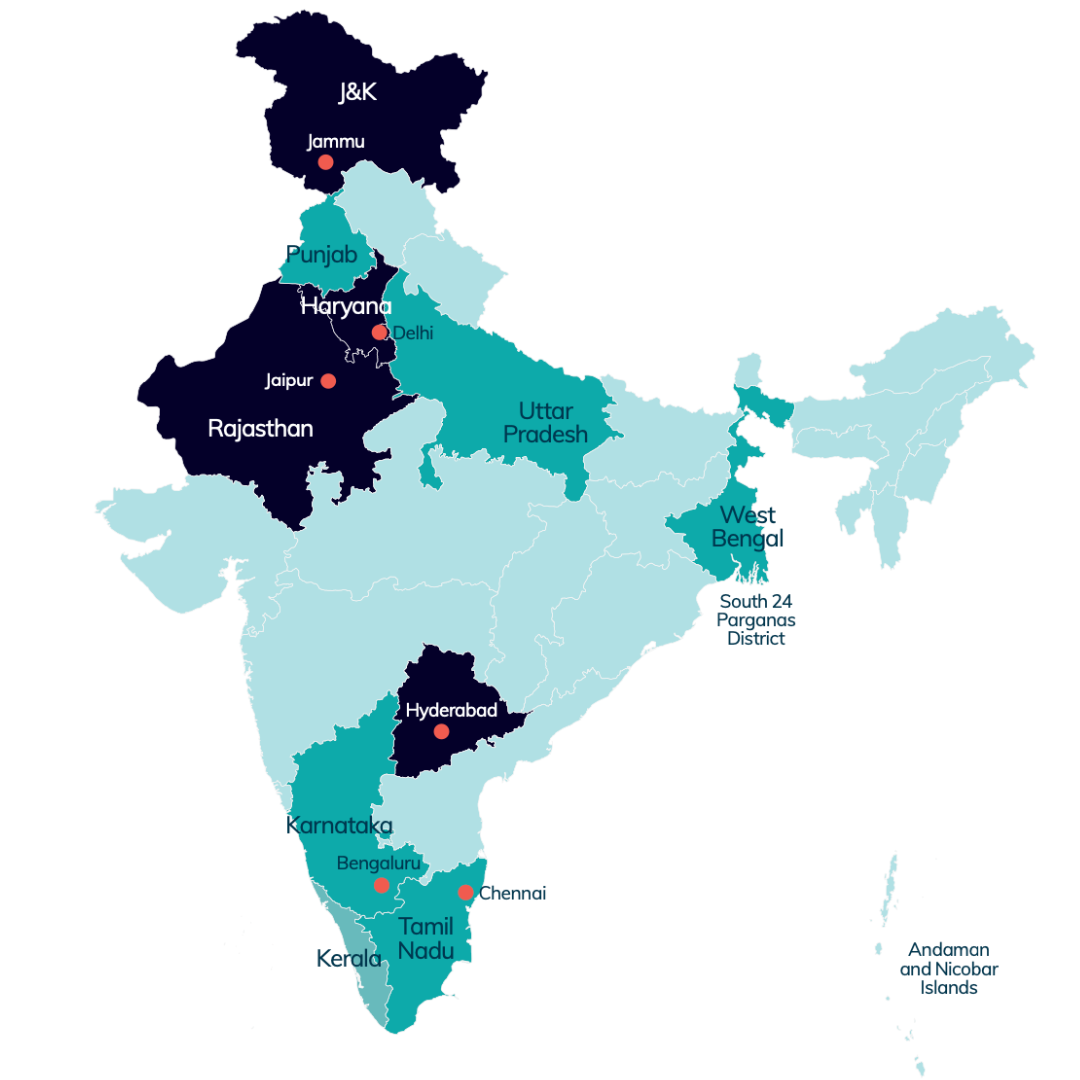

The Rohingya in India are largely concentrated in a handful of locations. Most live in the cities of Hyderabad, Jammu, Nuh, and Delhi. One Rohingya-led organization reported that there are more than 90 Rohingya refugee settlements across India. Rohingya, as a mostly Muslim community, tend to concentrate in areas of India with large Muslim populations. Hyderabad in southern India, which has a more than 40 percent Muslim population, has the largest settlements of Rohingya in India, with 32 slum-like urban settlement areas referred to as camps hosting approximately a population of 7,200 Rohingya.

India’s foreign policy towards Myanmar reflects a careful balancing act – one that tends to favor good relations with the military junta over denouncing the coup and atrocities. India shares a more than 1,000-mile-long border with Myanmar. While it is concerned about tens of thousands of mostly ethnic Chin refugees that have crossed into India since the coup, India also wants to maintain intelligence sharing with the Myanmar junta on Indian insurgents along the border. India also has economic interest in Myanmar, particularly concerning large trade and infrastructure projects central to its Act East Policy. It also has a broader geopolitical interest in good relations with the junta to counter growing Chinese influence in Southeast Asia.

India has denounced the violence in general terms but done little to pressure the junta. Indeed, India joined China and Russia in abstaining on a December 2022 UN Security Council resolution calling for an end to violence and release of political prisoners. India has also reportedly supplied weapons and military technology to Myanmar’s military junta.

India’s Refugee Policy

India does not have a domestic law nor consistent policy on refugees and asylum seekers and is not a signatory to the 1951 Refugee Convention and its 1967 Protocol. India’s Foreigners Act and Passport Act lump refugees in with other foreigners and require them to have valid documents, such as passports and visas, to stay in India. Without such documents, refugees are considered “illegal immigrants” and subject to detention and deportation.

India has provided documentation and permission to some groups of refugees directly, while offering Long Term Visas (LTVs) to others. In 2011, the Ministry of Home Affairs (MHA) set out a standard operating procedure to deal with foreign nationals who claim to be refugees, which included provision of LTVs where “prima facie the claim (of refugee) is justified, (on the grounds of a well-founded fear of persecution on account of race, religion, sex, nationality, ethnic identity, membership of a particular social group or political opinion.” But, in practice, this guidance is rarely followed, and many refugees remain vulnerable to criminal prosecution rather than refuge.

India has a history of hosting refugees even if not recognizing them. It has provided refuge to Pakistanis, Bangladeshis, Sri Lankans, Tibetans, Afghans, and Chin and Rohingya from Myanmar. The treatment of these groups has varied, however, depending on location, ethnicity, and the geo-politics of the time. Tibetans persecuted by the Chinese during times of tension between India and China, for example, found welcome and access to official residency, education, and work permits. Similarly, Sri Lankan Tamil refugees have been recognized and directly assisted by the government of India and the local Tamil Nadu state government. Chin refugees from Myanmar, though not recognized as refugees by India, have found support from the local government and community in Mizoram, with whom they share an ethnic affinity.

Other refugees are not recognized by India, but are allowed to register with UNHCR, which has had an office in the country since 1981, when it was allowed in to help with several thousand newly arrived Afghan refugees. These groups receive some assistance from UNHCR but none from the government of India and have been afforded fewer rights and recognition.

Today, 49,000 refugees are registered with UNHCR in India, mostly from Myanmar (29,361) and Afghanistan (15,053), with smaller numbers from several African and Middle Eastern countries. When combined with the Tibetans and Sri Lankan Tamils recognized by India, UNHCR reports a total of more than 213,000 refugees and asylum seekers in India. Local groups told the team there are many more refugees who remain unregistered, partially due to UNHCR being based only in Delhi.

Government policies and attitudes toward refugees, especially Rohingya, have deteriorated in recent years. The administration of Prime Minister Narendra Modi starting in 2014 has largely played to a nationalist audience fueling anti-Muslim and anti-refugee sentiments. This was highlighted in the passage of the Citizenship Amendment Act in 2019, which offered citizenship to minorities fleeing persecution in neighboring countries, but noticeably excluded Muslims. Right-wing agitators have regularly referred to Rohingya as “terrorists,” and political leaders, including the head of Modi’s Hindu nationalist party who referred to Rohingya as “infiltrators” and “termites” and threatened to throw them into the Bay of Bengal.

One of the key turning points came in February 2017, when a member of India’s ruling party, the BJP, petitioned the state High Court of Jammu & Kashmir seeking identification and deportation of Rohingyas from Jammu. The fervor around this petition and accompanying public campaigns led to many vigilante-style attacks and xenophobic comments against the Rohingya. Soon after, on August 17, 2017, India’s Minister of Home Affairs said that all Rohingya were to be deported and sent back to Myanmar. As one Rohingya leader told the team, this effectively “made all Rohingya illegal migrants overnight and led to negative hate campaigns from locals.” Around the same time, India stopped renewing LTVs for Rohingya.

In August 2022, the Indian Minister for Housing and Urban Affairs tweeted that Rohingya in Delhi would be provided with housing, basic amenities, and police protection. But the announcement was quickly denounced by the MHA along with a renewed call to detain Rohingya and send them back to Myanmar.

Efforts in India’s courts had previously prevented deportations of Rohingya refugees, but since 2017 the Supreme Court has upheld the government’s argument that Rohingya are “illegal immigrants” and failed to stop the deportation of at least 12 Rohingya.

Other policies, not necessarily aimed at refugees, have also effectively reduced their access to services. In September 2010, India introduced biometric identity cards, called Aadhaar cards, as a tool for improved economic inclusion and distribution of financial benefits. By 2018, more than 90 percent of the Indian population had one. Today, they are required for employment and to access many government services and subsidies. While Aadhaar cards are available to any resident of India, whether a citizen or not, refugees without government recognition or LTVs, are unable to get them. At first, some refugees were able to get Aadhaar cards, but by 2018 the MHA stated that UNHCR cards alone were not enough to obtain them.

In general, UNHCR cards that just a few years ago had provided access to some level of education and livelihoods and to protection from detention and deportation have been downgraded. In February 2023, in response to a Rohingya detention case, the Modi administration told the Delhi High Court that UNHCR refugee status without valid travel documents is of no consequence in India, leaving individuals who hold them subject to detention and deportation. Along with this, the COVID-19 pandemic led to India halting provision of exit permissions for refugees. Hundreds of refugees who had been vetted by UNHCR for resettlement and paired with third countries are still waiting to be resettled.

The Indian government has also failed to save Rohingya in danger at sea, even when within Indian waters. Tens of thousands of Rohingya have taken such voyages from Myanmar and Bangladesh in recent years. UNHCR estimates that at least 3,500 Rohingya took to sea in 2022, of which nearly 350 are believed to have died. Most try to reach Malaysia or Indonesia, but some have gone off course into Indian waters. Yet, the Indian Navy has ignored international obligations to save people in need at sea and done little more than provide some supplies and push the boats out of Indian waters.

Despite all this, India has signed international agreements on human rights (in 1948) and against torture (in 1997) and passed domestic laws on the right to life that apply to refugees. India has also served on UNHCR’s executive committee since 1995 and supported the 2018 Global Compact on Refugees, a non-binding framework described by the UN as “a unique opportunity to strengthen the international response to large movements of refugees and protracted refugee situations.”

Opposition leader Shashi Tharoor, in 2015 and again in February 2022, introduced the Asylum Bill of 2021 in the parliament seeking the establishment of an effective system to protect refugees and asylum seekers by means of a legal framework. The proposed legislation would, “provide clarity and uniformity on the recognition of asylum seekers as refugees and their rights in the country. It also seeks to end a system of ambiguity and arbitrariness which, too often, results in injustice to a highly vulnerable populace.” But there has been no movement or further discussion in the parliament over the Asylum Bill.

Deficient legal protections and the trajectory of India’s policy and practice on refugees has given rise to a series of challenges faced by Rohingya in India. These include threats of indefinite detention and deportation and limited access to education, livelihood opportunities, and healthcare

Main Challenges Facing Rohingya in India

One of the most frequently cited fears raised by Rohingya refugees interviewed by The Azadi Project and Refugees International was detention. Many of the interviewees cited direct knowledge of friends and relatives who had been detained and all cited a keen awareness of the daily risks of detention. Some interviewees were former detainees themselves.

While there is no official number of Rohingya in detention in India, local civil society groups, legal experts, and Rohingya-led organizations estimate the amount to be in the hundreds. Estimates are further complicated by a lack of clarity in what constitutes detention. What Indian authorities call “holding centers” act effectively as detention centers. In November 2022, UNHCR reported 312 Rohingya in immigration detention with an additional 263 in holding centers in Jammu and 22 in a welfare center in Delhi.

Specific reasons for detention are often arbitrary. In one case currently before the Delhi High Court, a Rohingya woman describes being called by her local Rohingya leader early in the morning to a remote location to fill out some paperwork. Upon arrival, she was detained by police and has been in detention ever since (see case study 1). While the motivation for such detentions is unclear, Rohingya and lawyers working with them suggested in interviews with the team that it was tied to political motivations to show toughness against Rohingya and, in at least one case, to fill the cells of a newly opened detention center in Delhi.

Many refugees mentioned that police often use local leaders as informers or have a quid pro quo arrangement of not detaining them if they can assist in getting other Rohingya detained. As one camp leader in Hyderabad told the team, local police pressure him to report on who visits the settlement and threaten him with detention if he does not report. If a new refugee is reported within a locality, they are vulnerable to detention. This leads to refugees in need of services, particularly new arrivals, staying in hiding unable to access hospitals or report crimes. As one young Rohingya woman in Hyderabad told the team, “people are living in a lot of fear here. Anything you plan on doing in life, you can’t.”

Rohingya refugees say these restrictions on movement have been getting worse in recent years, applying not only to movement between cities in India, but also between settlements within Delhi. One Rohingya woman in Hyderabad told the team, “It’s becoming like Burma with inability to move freely within the country.”

Conditions in detention were described as deplorable. One interviewee who had been detained for several months reported that people are held in rooms so tightly packed that detainees needed to take turns lying down to sleep. Other former detainees said the food was watery and full of dirt and dead insects. Most previously detained refugees complained of the lack of sunlight in the holding detention area. They said these conditions coupled with poor nutrition has caused many of them to lose their mobility, in some cases causing temporary paralysis. They described sickness as rampant and access to medical care arbitrary and limited.

“The staff at the detention center mix something in the food that makes us all sick. When we ask to see the doctor, we are not allowed to meet with the doctor ourselves. A police official accompanies us into the doctor’s room and speaks on behalf of us,” said a 23-year-old woman who was detained for more than 18 months. During that time, she lost her mobility, with her left side paralyzed. She says that she was ultimately released on medical grounds. “If we can’t even talk to the doctor ourselves to explain our symptoms, how are we expected to heal?” Visitation rights at detention centers are also limited and mostly at the whim of the civilian security personnel there. The centers are often remotely located and difficult for families to reach.

Separating Rohingya children from their parents during detention remains another grave challenge. A 23-year-old former child detainee told the team that while he was a teenager, he and his mother were detained for two years, during which he only saw his mother twice, for about ten minutes each time. His other siblings were also detained and sent to separate juvenile justice homes. None of them were allowed to be together. Remembering his time in detention, he broke down and added, “my younger sister is still in there.” A human rights lawyer working on the case similarly regretted, “We couldn’t get her out.” The lawyer, who has worked on refugee cases for more than a decade, told the team, “We have cases in West Bengal where the children are in a children’s home and the mother is in a detention center. Under the Juvenile Justice Act [of India], after five, they’re supposed to be separated, but the child cannot be separated if the child is breastfeeding or the child is dependent on the mother.” He also stated that the law “says very clearly, that you have to analyze the best interest of the child.”

Case Study 1: Detention of Shadiya Akhtar and the Forced Separation From Her Infant

Shadiya was 15 years old when she fled from her village in Myanmar along with her older sister Sabera. The increasing threat and incidences of sexual violence on women and girls left them with no other option. They traveled from Myanmar to Bangladesh, and after a few days there, they joined other Rohingya families to come to India. It was 2016 when Shadiya arrived in New Delhi, India as a 16-year-old. She followed protocol. She registered with the UNHCR to let the authorities in India know that she faced persecution in her home country and that she had come to India seeking refuge. She was given a UNHCR refugee card. Living in the slums of Kanchan Kunj in New Delhi was not easy. There were no toilets, and they lived on the little money that her sister’s husband earned from his work as a daily wage laborer. But Shadiya was content. At least she did not fear being brutalized and raped. In 2019, she married a Rohingya man and moved to another Rohingya settlement in Delhi and had a child.

In April 2020, a month after India announced a complete lockdown because of the novel coronavirus, Shadiya’s life changed completely. Shadiya was preparing breakfast that morning when a camp leader asked her to come immediately to the metro station to sign some papers. She left the tea water boiling on the stove and rushed to the station. Her son was spending time with her sister, and so she left him behind. It has been three years since that day, and Shadiya has not returned home.

Shadiya’s sister Sabera says that Shadiya and a few other Rohingya refugees were picked up by the police that morning while they waited to sign some papers. They were taken to a police station and from there to the detention center, known as a ‘seva kendra’ in New Delhi.

Ujjaini Chatterjee, a lawyer, is fighting the case pro bono. “[Shadiya] is one of the many poor and vulnerable Rohingya refugees, holding valid UNHCR ID cards, who’ve been detained through a clandestine and arbitrary ‘pick and choose’ process, without being informed of the grounds of such detention and without the opportunity to present their case and defend themselves,” she said.

Sabera had no idea where her sister had been taken. After days of searching, she was told about the detention center. She rushed with her nephew to see Shadiya there and to try and get her out. “They allowed us to see each other only for a few minutes. When I pleaded to let her son be with his mother, they refused and said that this is no place for a child.” The detention center as described by former detainees as a closed space where each detainee barely has any space to spread their mattress, let alone the ability to move around. One room houses the women and the other houses the men. There is no sunlight, the food quality is poor, and the portions are small. Shadiya fell seriously sick and has been complaining of severe stomach pain for the last few months. Her mobility has been affected, and she cannot move easily without support. She is now 22 years old and has spent three years away from her child, seeing him only for a few minutes during visits.

Meanwhile her three-year-old boy longs to be with her and wonders if she will ever be free again. But during his visits to the detention center to see her, he is gripped by fear. He asks his aunt Sabera, “What if they detain us as well and beat us?”

The efforts of local civil society actors and pro bono lawyers have helped to shine a light on these conditions and to secure the release of several detainees. Shadiya’s case led to a court-ordered inspection of the detention center in Delhi where she is being detained. Based on the report of the conditions at the detention center, the judge ordered an immediate renovation and improvement of the bathrooms and a complete health checkup of the detainee in question. India’s National Human Rights Commission should work with the UN Office of the High Commissioner on Human Rights to carry out an investigation of all detention centers.

Lawyers for the Rohingya also highlight that they face arbitrary and indefinite detention, a violation of international law. In several cases, Rohingya detained for being “illegal immigrants” have been held beyond their sentences. Indian authorities argue that they are awaiting deportation back to Myanmar, but this raises its own violations of international law and internal guidelines. The MHA standard operating procedure to deal with foreign nationals who claim to be refugees states that:

“in cases in which diplomatic channels do not yield concrete results ‘within a period of six months, the foreign national, who is not considered fit for grant of LTV [Long Term Visa], will be released from detention center subject to collection of biometric details, with conditions of local surety, good behavior and monthly police reporting as an interim measure till issuance of travel documents and deportation.”

But this is not being respected in practice.

Rohingya also fear deportation back to Myanmar, a fear based on real precedent and recent public policy statements. Despite the 2017 genocide and 2021 coup by the same military, dozens of Rohingya are believed to have been returned to Myanmar in recent years.

In 2017, public calls for identification and deportation of Rohingya in Jammu, followed by similar directives from the central government, led to a petition filed in India’s Supreme Court against deportation of Rohingya. Unfortunately, following another appeal in October 2018, the Supreme Court failed to stop the deportation of seven Rohingya men or to allow UNHCR to access them to determine if they were in need of protection. Again, in April 2021, following the arrest and threatened deportation of 170 Rohingya in Jammu, the Supreme Court accepted the government’s arguments that the Rohingya were a threat to national security and refused to stop deportation. India faced widespread criticism in April 2022 when it returned a 32-year-old Rohingya mother, separated from her children, to Rakhine state.

Actual and threatened deportations foster a sense of fear within the Rohingya community. For some, this has prompted decisions to move to other parts of India or to return to camps in Bangladesh. It has also added to the trauma of displacement felt by Rohingya refugee children. Fatima, a Rohingya woman in Delhi, described her nine-year-old daughter hearing calls for Rohingya to be returned to Myanmar and saying, “I hope they don’t send us there where they’ll chop off our heads. I hope we can stay in India.”

Returning Rohingya to Myanmar is a violation of the international principle of non-refoulement, which states that no government should return a person to a country where they are likely to face torture, cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment, or punishment and other irreparable harm. The Indian government has argued that this does not apply to them as they have not signed the Refugee Convention. But non-refoulement is also accepted as part of international customary law applicable to signatories and non-signatories of the Refugee Convention alike. Legal experts point out that India is a party to several international instruments referencing the principle of non-refoulement, including the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights and the Convention on the Rights of the Child. Further, as a signatory to the international Genocide Convention, India has a responsibility to work to prevent genocide, which should include not returning survivors to their perpetrators. Lawyers within India also argue that forcing Rohingya to return to life-threatening conditions in Myanmar would violate Article 21 of India’s constitution, which protects the fundamental right to life of all persons.

Under Indian law, all children ages six to 14 residing in India have the right to education. But this is not always recognized in practice. Rohingya cite their lack of access to the biometric Aadhaar cards as a common reason for government schools refusing to enroll Rohingya children. With a lack of clear guidance from the central government, local school officials often deny admissions. The government’s move to downgrade UNHCR cards, which had just a few years ago often been sufficient for enrollment, have further exacerbated the situation.

Some Rohingya children can access schools, often with the direct help of UNHCR or Indian NGOs working with the Rohingya community, but that is becoming increasingly difficult. Universal access to education for all children in India is also capped off after age 14, and Rohingya have not been allowed to sit for the examinations necessary to qualify for higher education.

Even when enrollment in government primary schools is possible, Rohingya refugees face long distances, language barriers, and maltreatment by other children, and sometimes teachers. As one Rohingya student told the team, “We have a constant feeling as being outsiders.” These challenges uniquely affect Rohingya girls. As one recently arrived mother described, it is difficult to send her daughter to school, so she plans to wait until she is of marriageable age and get her married. Girls also face pressures against girls’ education within the Rohingya community.

A handful of exceptions have been allowed for Rohingya taking the tenth grade state board examinations and finishing high school (see case study 2). The first cohort of Rohingya students allowed to sit for the examinations did exceedingly well and are now pursuing higher education opportunities. Some select Rohingya students have been awarded scholarships by private organizations to study in North American universities starting in the fall of 2023. This shows the potential for providing access to education for the Rohingya community and should be a catalyst for expanding such programs.

Case Study 2: Farhana Roshan’s Fight for Her Right to Education

Farhana Roshan was just nine years old in 2013 when her family moved to Mewat in northern India. Her father a martial arts instructor in Myanmar had been detained temporarily by the Myanmar military. Her sister who worked with UNHCR in Myanmar feared detention since many Rohingya who worked with the UN were being arrested. Her parents decided that to secure a safe and a better future for their children they had to flee. India sounded promising with a significant Muslim population and good educational institutions.

But when they got to India, Farhana and her siblings could not get admissions into any schools because of the lack of documentation or government identity cards. They had UNHCR cards, but that was not enough for access to educational institutions. Disheartened but undeterred, they moved to Hyderabad where an Islamic educational institution promised them admissions. Farhana enrolled in the third grade there and continued to study until her tenth grade. Three months before Farhana’s exams, her teacher told her that the state board was not accepting her examination request because of her refugee status and her lack of an Aadhar card. Farhana, along with a few more refugee students, were forced to leave school. Many of her fellow classmates who were forced to drop out were married off immediately, but Farhana’s parents did not give up. They, along with Save the Children, a child rights organization, advocated for her higher education. Finally, Farhana and three other Rohingya children were allowed to appear for the tenth grade state board examination.

Their persistence and hard work paid off. They became the first group of students in the Rohingya community in India to finish high school, and all of them scored highly. This infused new hope in the Rohingya community, and many others started dreaming of sending their children to school. Farhana herself carried out door-to-door campaigns in Hyderabad to encourage parents to send their daughters to school. She helped 50 girls enroll in schools. But soon, she and her friends faced another hurdle. Despite their good academic grades, none of them were offered admission to an undergraduate program. “We can’t give admission to Rohingya children because you do not have an Aadhaar card which is mandatory,” said Farhana, remembering the university response to her admission application.

After coming so far, Farhana was not ready to give up. She applied for scholarships to pursue her higher education in North America. Not only did she win a scholarship offered by a private organization, she also secured admission to the University of British Columbia and University of York to study political science. “I will surely go to Canada and start my studies, but it is not just about me. The children from my community who had big dreams and aspirations are demotivated. That’s why I am not happy but worried about others. I do not want others to stop their studies. Something needs to be done here in India,” says Farhana.

The introduction of Aadhaar cards and downgrading of UNHCR cards also has limited the ability of Rohingya to pursue formal employment. Most employers require an operational bank account and filing of taxes, which are not possible without an Aadhaar card. Many Rohingya find work in the informal sector but remain vulnerable to exploitation without legal recourse and face the ever-present threat of detention as they move to and from work. Their lack of access to bank accounts, again due to a lack of Aadhaar cards, further deprives them of a safe place to keep the money they do earn.

The most common form of employment, according to Rohingya interviewed, is day labor. Men in Hyderabad often work picking up garbage, while those in Jammu often work in the construction sector. Others work in meat factories. Rohingya women find informal jobs tailoring, making bangles, putting together flower garlands, peeling garlic, or breaking walnuts. Access to such work is often a determining factor for where refugees choose to live.

Some UNHCR- and NGO- supported initiatives have given Rohingya small grants and equipment to set up small shops or have employed them for community outreach. But steady employment remains the exception for Rohingya. One woman in Delhi, who had received support to open a shop, told the team that it had been ransacked and another time damaged in a fire. As of March 2023, she was yet to reopen the shop.

Most Rohingya in India live in slum-like settlements in urban areas such as Hyderabad, Jammu, and Delhi. Many of the shelters that Rohingya live in are constructed of wood, metal, and plastic sheets and placed closely together, leaving them susceptible to fires. Several fires have broken out in refugee settlements over the years, with some suspected to have been started on purpose by right-wing extremists. One study found that 12 mysterious fires broke out in Rohingya settlements across India between 2016 and 2021. After a fire in 2018 destroyed 50 Rohingya homes in New Delhi, a youth leader of the majority BJP claimed responsibility on social media.

The lack of safe running water and toilets in many of the settlements create their own challenges. Of 25 refugees surveyed by The Azadi Project and Refugees International in Delhi, Hyderabad, and Chennai, more than half said they did not have access to drinking water, and 93 percent said they did not have access to sanitation. Rohingya in Delhi described having to go to the bathroom in the same areas of their shelters used to prepare food and waiting until nighttime to dispose of the waste. Such practices and the dense living conditions and poor ventilation also increase the spread of illnesses.

Access to Basic Health Services

The lack of Aadhaar cards limits the ability of Rohingya refugees to access anything beyond basic health services. Rohingya can access government hospitals for basic treatments but must pay for anything beyond that. The survey carried out by The Azadi Project and Refugees International indicated that even though 92 percent of Rohingya refugees said that they have access to healthcare services, most of them cannot access specialized treatment or care.

The living conditions for Rohingya leaves them susceptible to a number of ailments including scabies, diarrhea, and respiratory infections. An inordinate amount of Rohingya reported suffering from kidney stones, possibly due to limitations in their diet and lack of clean drinking water.

Prenatal, postnatal, and early childhood care present a particular gap. Pregnant Rohingya women, mothers, and children are supposed to have access to immunization and nutritional support but are often denied this in practice. Several refugees told the team that they were unable to get ultrasounds during their pregnancies. According to groups working with Rohingya, some women have been turned away from giving birth in government hospitals. Some of those who were denied healthcare support had stillbirths or lost their babies during delivery.

At the same time, many Rohingya women, for various reasons, including cultural norms, financial challenges, and discrimination, choose to give birth at home. UNHCR and NGO partners have been working to raise awareness of the risks and counter the perceived stigma of hospital births with some success. A young refugee woman working with NGOs in Hyderabad highlighted success in these efforts as more Rohingya women have been giving birth at hospitals in recent years.

But Rohingya are not always given birth certificates. A new mother told the team that this was the case even though she gave birth at a hospital. At times blank birth certificates are issued that recognize a birth but have no additional information about the parents or the child. Birth in India does not automatically grant children citizenship, but identity documents are important for accessing services.

The COVID-19 pandemic also exposed and exacerbated the vulnerabilities of Rohingya refugees in India. Rohingya were unable to access treatments or government assistance programs. Initially, this also meant that Rohingya and other refugees in India were unable to access free tests and vaccinations. The pandemic also affected the ability of Rohingya to earn income to access private hospitals. A survey by the refugee-led Rohingya Human Rights Initiative in August 2021 found that nearly 56 percent of Rohingya refugees lost employment due to the pandemic.

Risks to Women and Girls

Rohingya women and girls face a host of challenges based on their gender and prejudices ingrained both within the Rohingya and host communities. Many Rohingya women have experienced intimate-partner violence or child marriage. Some have been trafficked into India either directly from Myanmar or via Bangladesh and sold to older men as brides. The fear of being detained or deported prevents these women and girls from reporting any violence or crimes against them.

Lack of legal status or income also limits access to sexual or reproductive health services, pre-natal and post-natal care, or treatment or support for gender-based violence. The lack of livelihoods and access to higher education for Rohingya in India, coupled with a notion that girls would be safer from sexual assaults and violence if married, results in families wanting to marry off their daughters early and not send them to school.

The general living conditions for Rohingya also uniquely challenge women and girls. Lack of toilets and showers make menstrual hygiene management next to impossible. Many women and girls therefore suffer from infections but do not seek help because of the associated stigmas.

Shrinking Support for Rohingya in India

There are several international, local, and refugee-led organizations and individuals working hard to support the Rohingya community in India. Donor countries including the United States and several European countries have provided funding. UNHCR and its partner organizations provide services ranging from food distribution to education and psycho-social support. In Hyderabad, NGOs run child-friendly spaces that offer skills-building and language assistance and provide cash grants and equipment like push carts and small refrigerators to support Rohingya setting up small shops.

Community health volunteer programs also carry out home checks and offer support for referrals and transfers to government hospitals as well as raising awareness about gender-based violence. Pro bono lawyers are supporting the Rohingya in taking cases to the courts to challenge detention and deportation. And, as highlighted earlier, community efforts have helped to push through the first cohort of Rohingya taking higher-level exams in India.

However, the space for these efforts is shrinking. Representatives of NGOs and civil society with whom the team spoke all cited fears of retaliation for speaking up too loudly on behalf of the Rohingya. Many organizations who have either directly criticized Modi or his policies, including regarding Rohingya, have lost their permissions to receive foreign funding through the Foreign Contribution Regulation Act (FCRA). Rohingya civil society leaders described fewer activists coming to Rohingya settlements out of fear of government retaliation. Similarly, Indian NGOs told the team that they have avoided pursuing projects to assist Rohingya, considering the risk of endangering FCRA permissions and undermining other projects too high. As one NGO representative said, “everyone is afraid to talk to each other because of FCRA,” describing it as “a huge deterrent to what kind of work organizations are willing to do.” They then stated bluntly, “we do not do advocacy, because we would be shut down.”

UNHCR and Resettlement

Similarly, UNHCR’s role has remained very limited, and the space provided to them to carry out protection and resettlement services—or even relief aid for the Rohingya—is either shrinking or non-existent. UNHCR representatives have been unable to meet with high-level Indian officials or to visit Rohingya held in detention and have been reserved in speaking out against detention and refoulement of Rohingya back to Myanmar. This has led to widespread criticism and frustration with UNHCR’s role in India by NGOs and refugees.

As mentioned earlier, UNHCR cards are not recognized by the government. India is also not allowing exit permissions for refugees who have completed refugee status determinations with UNHCR and gained approval from third countries for resettlement. This policy started because of COVID-19 but has yet to change. Civil society groups familiar with the process told the team there are at least 300 refugees waiting on resettlement. When combined with their families, that number is likely more than 1,000. Most of these are Chin refugees, but a small number of Rohingya are also awaiting exit permissions to resettle.

The reasons for the refusal of exit permissions are unclear. Some observers cite technical difficulties regarding the inability to provide legal documents since the onset of the Aadhaar system or the expiration of medical exams since COVID-19 hit. Others say that the government fears creating a pull factor for refugees coming to India in hopes of being resettled. The unfortunate reality is that the vast majority of refugees, whether in India or globally, will not be resettled. On average, less than one percent of refugees are resettled each year. Any sense of a pull-factor is better addressed by improved messaging to refugees and expectation management about the long odds, not by blocking the few opportunities for resettlement. The pull-factor argument also ignores the very real push-factors of the genocide and increasing insecurity and desperation in the camps in Bangladesh.

Instead of refusing exit visas, India can help facilitate more resettlement opportunities from India by advocating for increased resettlement from host countries with ally countries like the United States, Canada, Australia, Germany and other European nations at summits like the G20 summit. This will also show that India recognizes the push-factors of the genocide and is helping facilitate permanent resettlement solutions for those impacted by it.

Donors and UNHCR should further engage India at the highest levels to counter these troubling trends. If there are technical difficulties to resettlement, addressing them should be prioritized. UNHCR’s high commissioner Filippo Grandi should visit India to raise these issues and facilitate immediate steps to increase exit permissions and resettlement, access to detainees, and non-refoulement and a longer-term dialogue on formalizing the status of refugees in the country.

A Way Forward

Many of the challenges facing Rohingya in India can be addressed by formal recognition of their status as refugees with a right to asylum rather than as illegal migrants. This can happen by India signing the Refugee Convention and the establishment of a domestic law on refugees and asylum, as proposed in the draft bill introduced in February 2022. Given the enthusiasm of the Modi administration on their international commitments, it would be a step in the right direction for the government of India to live up to their commitment as a signatory of the Global Compact on Refugees and bring in a refugee law that protects refugees and asylum seekers on an expedited basis.

Short of these larger changes, simple acknowledgement of residency would go a long way to addressing the challenges Rohingya and other refugees face in India. This could be done either by government recognition of UNHCR cards as sufficient for accessing basic education, work, and health services or provision of Aadhaar cards to refugees as proof of residency. More immediately, the government could start by resuming issuance of LTVs. At a minimum, the Indian government should refrain from indefinite detention and deportation of Rohingya. It should also lift barriers to the limited support already available to refugees, both in terms of allowing local NGOs to work with refugees and allowing UNHCR to resettle them. India should also live up to regional agreements on search and rescue and safe disembarkation for Rohingya found at sea and encourage other regional governments to do the same.

Better treatment of refugees is in India’s interest. A written policy on refugees would serve to better protect vulnerable populations and give the government more global credibility. It would also serve national security interests, as new arrivals would be officially documented and not incentivized to remain under the radar. Such policies should also interest India as the world’s largest democracy and as a country seeking greater global and regional leadership. As a longtime host to people seeking asylum and an active contributor to the development of the Global Compact on Refugees, India has shown some proclivity toward such leadership. The Global Refugee Forum later this year, meant as a vehicle for assessing shared responsibility for refugees, provides an opportunity for India to showcase improved refugee policies. Similarly, India’s leadership of the G20 this year brings extra attention to its policies on issues affecting countries across the globe, including unprecedented levels of displacement.

The United States and likeminded countries should engage India on refugees at the highest levels and ensure that treatment of Rohingya and other refugees in India are among the key points raised in bilateral discussions. This should include when President Biden hosts Prime Minister Modi at the White House this summer and when President Biden visits India for the G20 Summit in September 2023. The United States should build on its leading role in funding the humanitarian response for Rohingya refugees and strengthen its message by addressing shortcomings in its own asylum policies, particularly along the southern border with Mexico. Steps taken to outsource asylum procedures both violate the United States’ own obligations and undermine calls for responsibility sharing on refugees globally. It should also increase the number of refugees it resettles, which remains far below the 125,000 authorized by the Biden administration for 2023.

In the longer term, the United States and likeminded countries must also engage India toward addressing the root causes of displacement in and from Myanmar, namely the actions of the military junta. Rather than abstaining within the UN Security Council, India should speak out and use diplomatic pressure to urge an end to violence and support for accountability.

Conclusion

Treatment of Rohingya in India is a microcosm of the treatment they are facing across the region. While the root of the challenge lies within Myanmar, countries of first or second refuge are failing to sufficiently protect Rohingya refugees. The restricted rights, harassment, and detention Rohingya face in India and other countries of refuge also increasingly echo some of the very same persecution they have faced in Myanmar. Rather than re-victimizing Rohingya, India and other countries should be doing more to protect them and to support the Rohingya community in building toward a better future.

The Azadi Project and Refugees International would like to thank Kaynat Salmani, Sabrina Churchwell, and Saranya Chakrapani for additional inputs and interviews informing this report.

Featured Image: A Rohingya woman gazes outside her window at a Rohingya refugee settlement in India. © The Azadi Project and Refugees International.