By Alison Waldman

November 2020

“I think I’ll need to change my name if I ever get to the US. It may frighten people,” was the first thing fourteen-year-old Jihad said to me. As an unaccompanied minor, his name was his only remaining connection to his parents and former life in Syria, both of which he had already lost. His name, he explained, does not signify war or violence. Rather, it refers to a “great accomplishment resulting from a struggle”. His mother was in labor for thirty hours. He was her “Jihad”. So much loss for a child. How unfair to even contemplate relinquishing the beautiful name chosen by his parents. I choked back tears, struggled to find comforting words and was grateful for the healing and relaxing experience that my drawing workshop would hopefully provide.

There is a familiar bustle and rhythm to life in a refugee camp that is at times not altogether different from life outside the barbed wire. Meals need to be cooked, clothes need to be washed, diapers need to be changed, wood for the make-shift mud ovens needs to be chopped. Routines, laughter, games to occupy the time — all offer an occasional sense of normalcy. But first impressions mask the harsh reality of life in refugee camps: the overcrowded conditions, inadequate shelter, lack of privacy, susceptibility of women and children to sexual assault, shortages of water, food, toilets and showers, and of course the interminable uncertainty. Yet the refugees I have had the pleasure of meeting are some of the most positive, resourceful and self-reliant people I have ever encountered. And none more so than the unaccompanied children I worked with in the spring of 2019 in Lesvos, Greece — the Gekko Kids.

There are approximately five thousand unaccompanied minors living in Greece. Some are hoping to reunite with parents, older siblings or family members in northern Europe; some are sent by their parents to escape violence at home; some are separated or orphaned en route to Greece. Among refugees and asylum seekers, these children are among the most vulnerable to physical and sexual violence, rape and trafficking. Many run away from the camps, fall prey to traffickers or are living in dangerous conditions in order to avoid deportation. The Moria Refugee Camp in Lesvos was home to the largest number of unaccompanied minors, over one thousand, before it burned to the ground in September earlier this year. Most were boys between the ages of fifteen and seventeen. Many girls were pregnant or had infants as a result of rape in the camps. Months turn into years for these children, as delays in the registration and family reunification process are compounded by the lack of legal support and the overburdened asylum service. And while Greece has urged the EU to share the burden of relocating and resettling these unaccompanied children, only a handful of countries has pledged to receive some of them.

Afghanistan, age thirteen. He is a talented photographer, soccer player and taught himself fluent English.

Afghanistan, age thirteen

Afghanistan, age fourteen

Afghanistan, age fourteen

Afghanistan, age fifteen

Afghanistan, age sixteen. Hamied spent over two hours drawing with meticulous attention to detail. Modest about his obvious talent and creativity, he was hoping to someday study art and filmmaking.

Afghanistan, age sixteen

Afghanistan, age sixteen

Afghanistan, age sixteen

Afghanistan, age fifteen

Afghanistan, age fifteen

Guinea, age sixteen. He spoke about his love for his mother and recalled her strong shoulders, her colorful dresses and the sound of her voice.

Guinea, age sixteen

Determined to address the lack of access to safe living conditions and an education, the nonprofit Together for Better Days launched a magical and transformational program for the hundreds of unaccompanied children in Lesvos. Their Gekko Kids program offered the physical and emotional space for unaccompanied teens to connect with one another and learn, among other things, English, computer skills, photography and math from certified volunteer teachers. And perhaps serendipitously, only a few blocks away two women, who founded and operate the Poliana Arts Center, decided to offer art workshops for these refugee teens. Katie and Anique recognized the restorative power of creative expression to heal the emotional and physical trauma experienced by these children.

On June 1, 2019, I walked into Poliana’s cozy stone art studio and met my students, thirteen boys ranging in age from twelve to seventeen. (Most unaccompanied minors are boys, as it is considerably less safe for girls to travel on their own.) Equipped with a translator and hundreds of markers, acrylics and watercolors, I slowly explained why I had traveled from Washington, DC to meet them.

I had repeatedly rehearsed in my head what I would say to and request of the thirteen students seated at tables in the Poliana Art Center. I told them that this was an opportunity for them to speak to the world via their art. What did they want the world to know about their lives and their hopes and dreams? If they could say one thing to people everywhere, what would that be? I told them that their drawings would be part of a traveling exhibition to promote awareness of the continuing and worsening refugee crisis and to encourage tolerance towards the millions of forcibly displaced migrants. I was not surprised by their perplexed stares when I explained that many people in the US do not realize that the crisis remains unresolved. And I hoped that they would be pleased and proud that their artwork would travel to universities, nonprofits and businesses throughout the US — a journey to open hearts and change minds. The irony, sadly, that their artwork would travel to places they would likely never see was not lost on me.

I had envisioned a noisy room full of typical teenage chatter but instead was surprised by the silence in which they seemed most comfortable. Perhaps a much-needed respite from the chaos and unpredictability that permeate their lives. I also expected that they would need time to think about what they wanted to draw. Yet they began to sketch immediately, as if their bottled up parts had suddenly been uncorked. Released from years of muteness, their stories and journeys spilled onto paper. And then it dawned on me. They had begun conceiving their messages to the world years ago.

When the middle school he attended in Syria burned to the ground with most of his friends inside.

When the Taliban came to his northern Afghanistan town and “removed” his teenage sisters.

When at the age of eleven and oceans away from Lesvos he witnessed his mother’s murder.

When he had almost made it to Lesvos and he was robbed of all of his belongings, including photos of his family, on the Turkish side of the sea.

When the overcrowded rubber dingy he was in capsized in the Aegean Sea and he watched helplessly as a toddler slipped under the water.

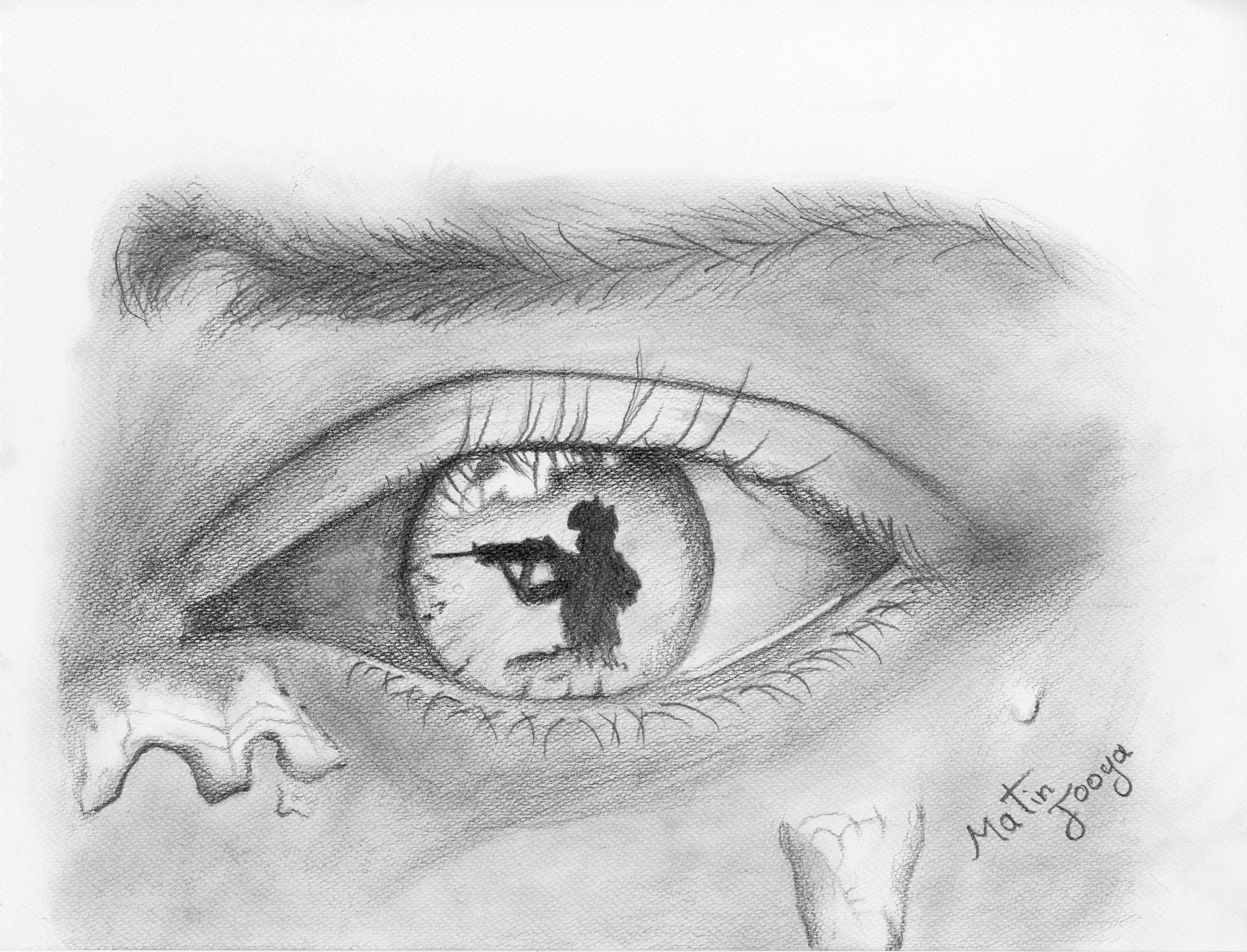

And despite the availability of watercolors, acrylics and colored pens they gravitated towards the pencils. In truth, the messages in their drawings need no embellishment. Perhaps years of deprivation had taught these children a truth that often eludes so many— that sometimes less is indeed more.

Note: Jihad has not changed his name, as it would complicate the paperwork essential to the asylum process. Only a few of the teen artists remain in Lesvos. Most of them were transported to mainland Greece or flown to countries in northern Europe following the fire at Moria. As of the Fall of 2019 Gekko Kids is no longer operational in Lesvos. Together for Better Days has relocated to mainland Greece. The exhibition, Hope in the Face of Despair: The Power of the Pencil will be debuted and displayed at Hamilton College in Clinton, New York in 2022.

Alison Waldman is a Washington, DC-based international aid worker and refugee resettlement and employment specialist. She has worked with the IRC, HIAS, Lutheran Social Services and Catholic Charities to resettle refugees throughout the DC-Baltimore region. Her first trip to Lesvos was in January 2016 and she is looking forward to returning post-covid.